Concerned about vendor costs when it comes to producing technical documentation for the web? You might want to take a look at our recent article in EE Times reprinted below. (See the original article at https://www.embedded.com/free-tools-build-multi-format-documentation-systems/.)

Using open source tools, it’s possible to create a documentation system that can present the same information on large and small displays.

In a recent column on Embedded.com, Max Maxfield blasted the slapdash guide that accompanied a module he’d purchased and asked why so many manufacturers neglect documentation until the last minute (see Basic documentation—is it too much to ask for?). Was a budget or staff ever too big to blame for procrastination? Yet even a conscientious development team can’t supply useful help without a well-organized system in place to record work in progress, edit the information, and publish documentation in whatever formats are required for easy access. There are many ways to build such a system based on commercial software, which can be expensive, or by using free and open-source tools.

My firm has generated documentation for more than 30 years for semiconductor fabrication equipment, graphics processors, test instruments, network gear, CAE tools, and so forth. We’ve rescued clients on the brink of product rollout and worked on multiyear projects from the inception. The best path for any manufacturer, whether a startup or an established enterprise, is—before product development begins—to put in place internally a documentation system tailored to deliver information in ways most convenient to customers. Let’s consider a straightforward, low-cost approach one company used to get up and running quickly.

A long-established manufacturer that produces biomedical instruments and related assays for disease screening sought a documentation system that could output product literature in both PDF and in HTML format for Web presentation from the same source text. The company had built an extensive library of instrument manuals and detailed guides for its many assays, all of which had been produced using the Adobe page-layout tool, FrameMaker, and needed a flexible platform for generating searchable new documents for electronic display that would be virtually identical to their print counterparts. The content, as well as the structure of any of the documents in either format, requires FDA approval subject to stringent federal review.

The project was fast-tracked by a battery-backed portable instrument that was in development. This instrument tests biological samples in the field to quickly determine whether patients have HIV, certain influenza strains, or other infectious diseases. It is intended for use at remote sites and in neighborhood clinics, especially in developing nations, where there may be limited electrical power and economy is paramount. The user interface is a cell phone controlled by a dedicated application, unlike other instruments made by the company, which communicate with a laptop or desktop computer.

Instructions for operating the instrument, as well as the guides for the assays it runs, reside in the cell phone, except for brief startup steps on paper to turn on the phone and open the app. Assay guides run 30 to 40 pages in PDF, posing a challenge how to present the material legibly on a display that is less than six inches long by three inches wide in a structure that could be easily searched.

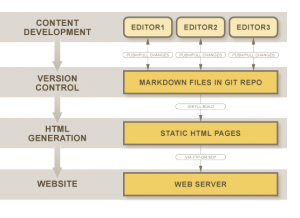

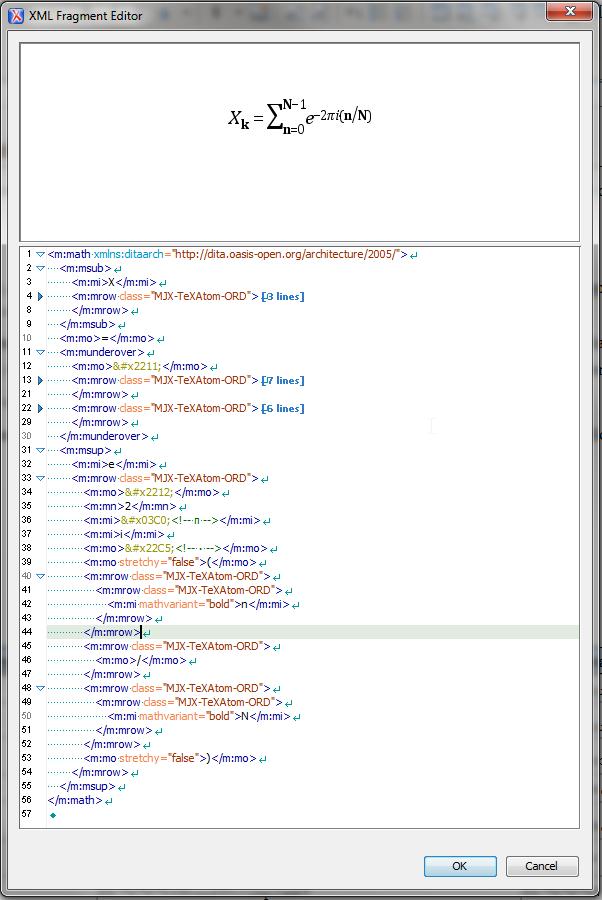

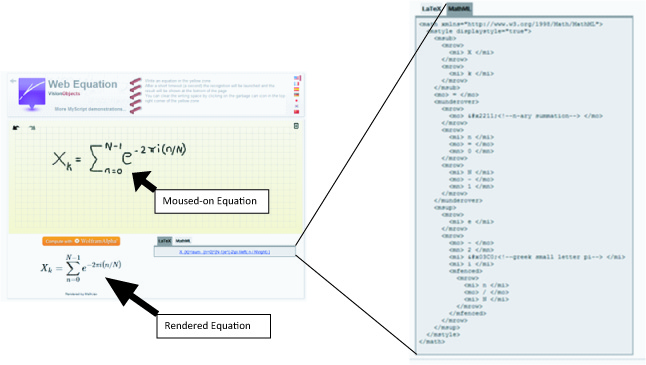

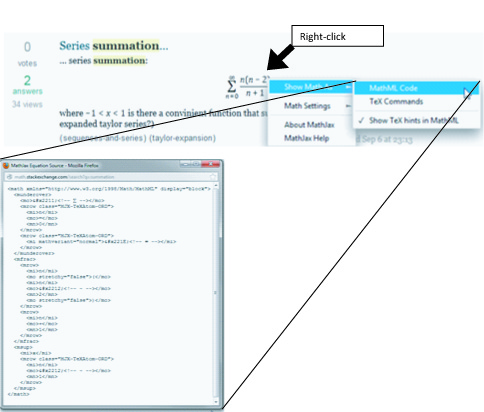

An open-source standard, DITA (short for Darwin Information Typing Architecture), was chosen as the foundation for the documentation system. DITA, which was originated by IBM, defines an XML architecture for publishing information in multiple formats for print, Web display, and retrieval on mobile devices. Document outputs in the various formats are implemented using the DITA Open Toolkit, a collection of open-source software programs. The upshot of DITA is that content is distinct and independent of how it will be presented, with reordering and reuse in mind.

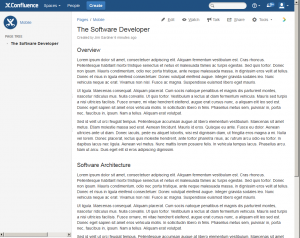

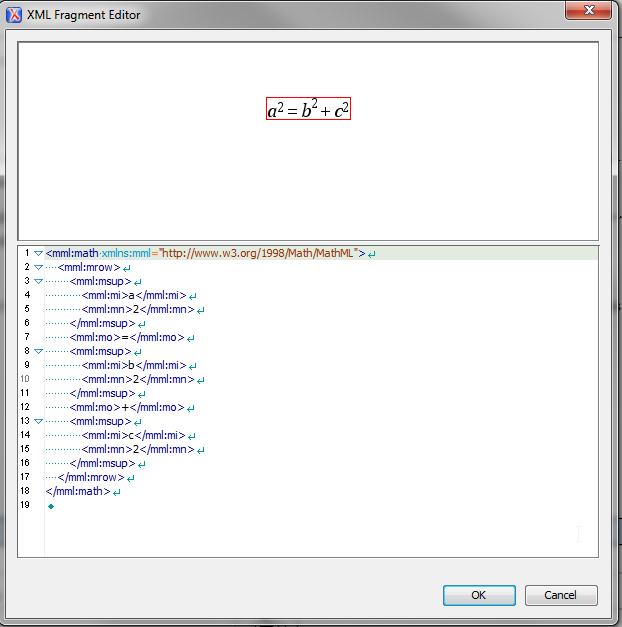

Some existing assay guides had to be translated from PDF for use with the portable instrument. The content was extracted in essentially a cut-and-paste operation and then tagged in a DITA XML markup. Formatting templates were created so the documentation system would strictly adhere to the FDA-approved style for the company’s literature in PDF, and then the toolkit was used to output files in HTML5. The toolkit can render DITA XML files for output in several formats, including XHTML, HTML5, PDF, and others. Although FrameMaker, the page-layout program, also can export files in HTML, it would actually complicate building a Web portal for documentation: you can’t make inter-document links, for example, or readily create a hierarchy for building a documentation site.

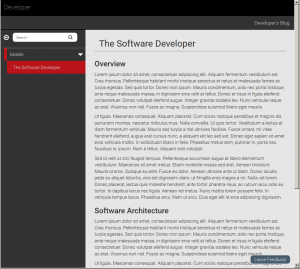

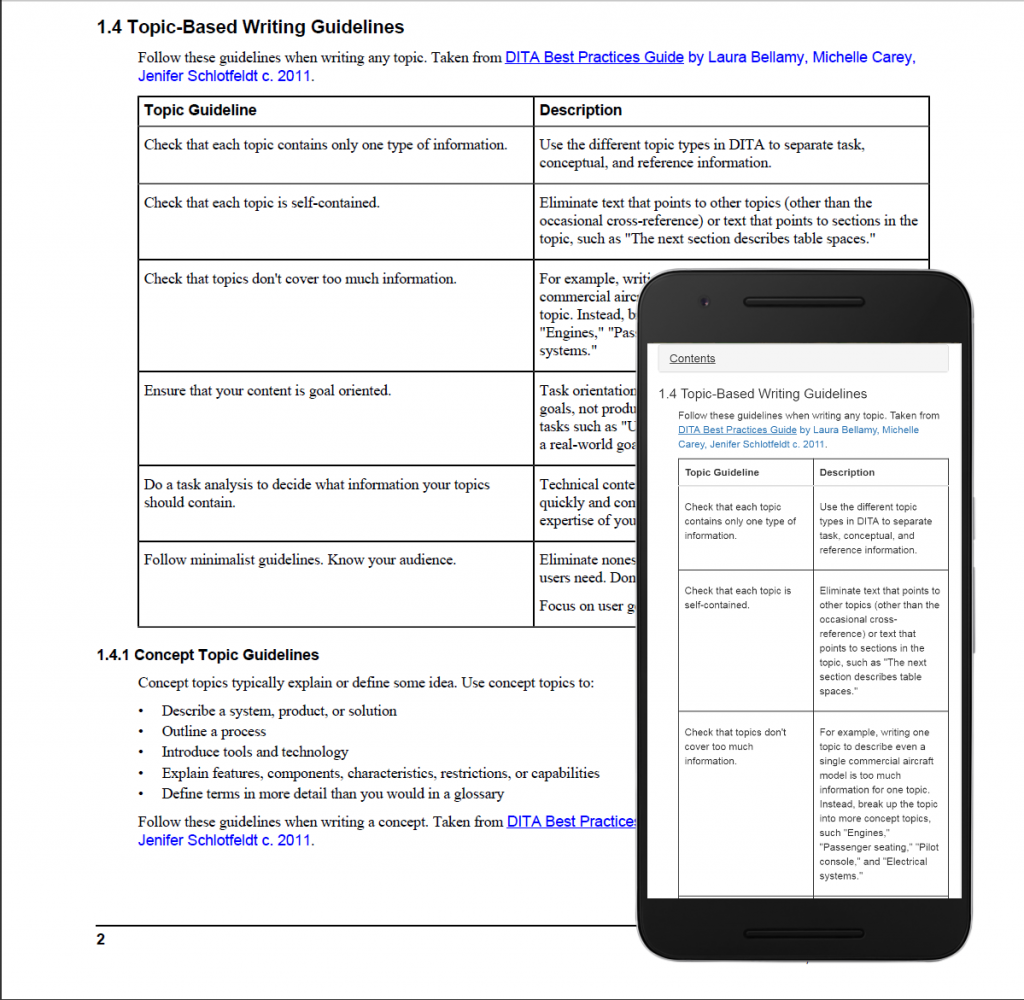

Arranging the HTML5 output from the documentation system for display on the cell-phone screen involved Bootstrap, a framework for automatically scaling websites for viewing on phones, to tablets, to desktop computers. Bootstrap, which is a collection of cascading style sheets and JavaScript, employs a grid for defining how information should appear within different screen dimensions. For a large 4k display, for example, content could be presented in multiple columns, if desired; for smaller screens, how elements shrink, are rearranged, or remain visible can be defined.

In the case of the project we are discussing, content is displayed in a two-column makeup on a widescreen, and in one column on the cell phone with a collapsible table of contents at the top. For the phone, each document section amounts to a Web page. Information is displayed one section at a time. There is always a table of contents that can be expanded for quick and easy navigation through the document. If the table of contents is collapsed, the material for one section is displayed and—when read to the bottom—there is a link to go to the next or previous sections.

During the development of this system, a technical detail tied to regulatory acceptance arose that had to be resolved. When documents are authored in FrameMaker, tables that continue from one PDF page to the next repeat the table title. However, the PDF outputs yielded by the DITA process don’t repeat table titles from one page to the next—just the table headers.

Another tricky issue, general in nature, was how figures are numbered in the HTML5 output from the DITA toolkit. The PDF output is fundamentally a continuous scroll, but the HTML5 output is broken up into sections and the toolkit does not number figures in succession but starts again from 1 in each section. The fix involves adapting a bit of code from the PDF process. Basically, the PDF process produces a file that merges topics mapped in DITA, but HTML documents are collected assemblies of the topics, each of which remain in a separate file. The PDF process merges everything from the DITA map, everything from the document hierarchy, rolled into one big file that is used to count such things as figures. The code that was appropriated from the PDF process modifies the HTML process to maintain the consecutive numbering of figures.

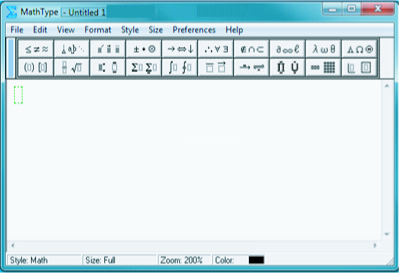

Any plaintext editor can be used at the front end of such a system to create content, though a modest investment for Oxygen, XMetaL, or other commercial XML editor is worthwhile. Those programs are much less expensive than FrameMaker, which is the conventional workhorse for document creation.

Startups, especially, who want to build a flexible documentation system quickly and inexpensively that can publish material in multiple formats from the same content can benefit from this approach, which is based on free and open-source software tools. The only problem remaining, therefore, is procrastination.